|

What a small resting place in a subdivision says about our past and why it’s a cautionary tale for the future.

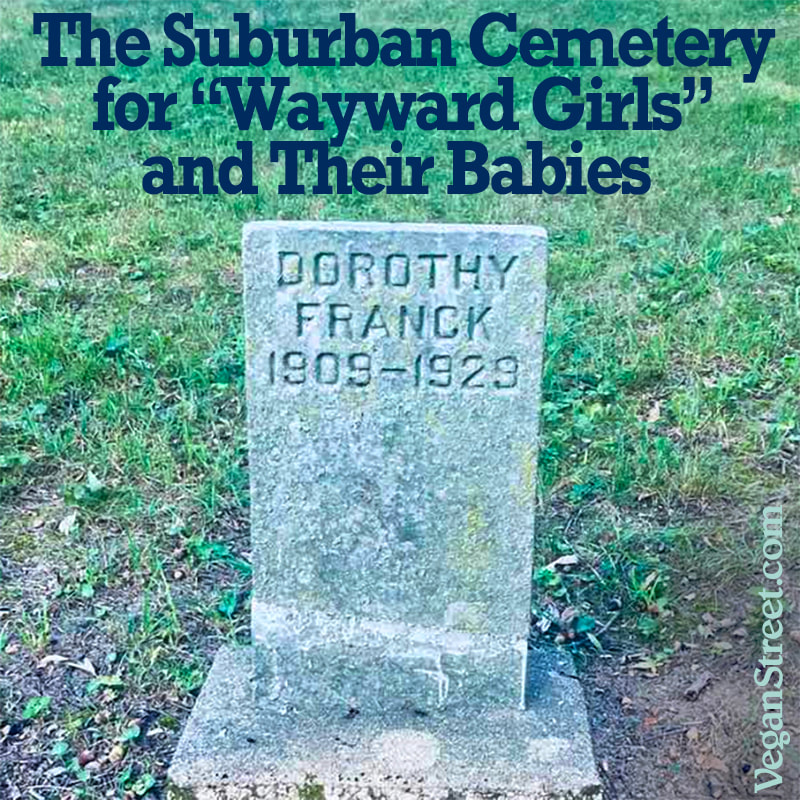

This past Sunday, I was feeling that familiar invigoration I can always rely on in early autumn, as the leaves are just on the verge of changing and the earliest of households start displaying their Halloween decorations. I convinced my son and husband that we should drive out to Geneva, IL, a quaint, verdant river town in the western suburbs of Chicago, about 45-minutes west of us. We trek out here a few times a year to take in the riverwalk, enjoy the boutiques, and breathe in the air of a fresh season. On Sunday, I got that urge again and my guys were on board so we charged our phones, packed our drinks and set out for Geneva. Just before we left, thank goodness, I remembered that there was a place there that I wanted to see in person, one that had not been on our itinerary before. It was the tiny cemetery of 51 graves on what was once part of the 94-acre property of the Illinois State Training School (ISTS), also known as the State Industrial School for Delinquent Girls or the Illinois State Training School for Delinquent Girls (among other appellations), which was in operation from 1894 until 1977. Just outside the gates of the now-demolished institution you fill find this small cemetery, improbably nestled between and behind two large homes in an affluent subdivision called Fox Run. I had heard of the cemetery before here and there and seen some photos of the spare, old gravestones. I also knew that the cemetery was in an unlikely setting but that didn’t stop me from wondering if our GPS had failed us as we drove around cul-de-sacs and saw children riding their bikes and walking dogs in this decidedly residential setting. When my maps program said we had arrived and we were, in fact, between two large, manicured lawns, I stepped out to look around but I was doubtful. Where would it be? After walking around a bit more, I saw the iron fence and called out for my husband and son, still in the car, to join me. Somehow or another, this was it. We walked over to the fence, first passing a plaque, which reads, “Beginning in 1894, this land was used by various government agencies as a center for ‘wayward girls’. The colonial-style cottages, service buildings and fences are gone, but these 51 graves remain. These graves are a testimony that they are no longer wayward but home with their Creator.” The plaque ends simply: “May God’s peace be with their souls.” The first thing I noticed after walking through the gate was how uniform the simple concrete markers were, bringing to mind photos I have seen of the rough gravestones for the Civil War dead. The next thing I noticed before I began looking at the stones was a tall, utterly majestic oak tree, her branches offering a quiet green canopy for us, over much of the cemetery. The acorns crunched under our shoes. That was the only sound in the cemetery — the crunching, that familiar autumn sensation— aside from the occasional words between us as we took the space in. We split up and walked on our own. At first when I saw some gravestones for boys, I was confused because I knew this was an institution for girls but then I noticed how long they were alive: These graves were for babies or newborns. They are clustered together in one section of the cemetery. The adults, sometimes their mothers, are buried near one another elsewhere in the cemetery. The adults were barely adults themselves: The gravestones indicate that age 20 is about the oldest the dead in this cemetery lived to be. That makes sense, though, because ISTS was an institution specifically for minors. The inmates were juvenile girls, some as young as ten, to the age of 18, though some were younger and many were a little older. Most had been sent because they were sexually active or pregnant; later research found that more than 74 percent of inmates were incarcerated at ISTS, which housed up to 400 girls at a time, for reasons of “immorality,” the unspoken code for pregnancy, sexual precociousness or suspected sex work. As the plaque at the cemetery references, they were “wayward” girls, wayward enough to have been convicted in juvenile court. In the mental and physical examination records, it was noted that some were disobedient. Some were described as feeble-minded, which could mean anything from a speech impediment to being terrified of their interrogators. Some were deemed to be incorrigible. Some were found have unpredictable mood swings. Some there had been convicted of truancy. Some were labeled as sexual deviants, a code for lesbians or even non-virgins. Many were runaways from abusive homes. Most were willful. All had been found guilty of violating society’s norms for girls. All were also poor. Middle class and wealthy girls who ran afoul of social norms weren’t given a free pass, but they also weren’t sent to institutions like this one. I have no doubt that some of the girls incarcerated at ISTS over its 80+ year history were indeed mentally ill and genuinely needed help, but that was not what the institution or even society offered at the time. Ophelia L. Amigh, a one-time Civil War nurse who was superintendent of the institution for 16 years, ruled with an iron fist until she was ousted due to vaguely-worded controversies in 1910. To reinforce the obedience to the matrons, girls deemed rebellious or sexually active with each other were sent to the hole (solitary confinement), subjected to “hydrotherapy,” which meant having their bodies repeatedly dunked in cold water, there were well-worn straps and a riding crop, as well as a chair built by the institution’s carpenter, much like a stock from the Puritan days, where the person it is only had their head poking out. They lived in small cells with just a cot and a barred window. I call them inmates intentionally. Many committed to ISTS ran away and were returned; many ran away and were never found. Some like 20-year-old Sadie Cooksey died by electrocution on the third rail of the nearby railroad line as they attempted to flee. The heaviness and the stillness of this residential cemetery is something that sat heavy on my chest after we’d left. Three days later, it’s still pressing down. Inside the cemetery, there was almost the feeling of a gasp that couldn’t be released while I walked through, looking at the stones, taking photos, a kind of suspension. I have visited many old cemeteries and this one probably had the most palpable feeling of sadness. Then again, it could be because of what I know of the place where they died. There is also the unavoidable cautionary tale of this burial ground. All were indigent, all were society’s outcasts, most were teenagers or babies. Some were Black and kept in segregated cottages, others were mentally ill and abused. All were prisoners without resources, and there were some for whom this hellhole was an actual step up from the abuse they faced at home. While the institution has been bulldozed and an affluent subdivision has been planted over it, and the cemetery certainly looks like something from a bygone era, is the ISTS really just a sad chapter of our history? With states having more to rights over the bodies of pregnant people themselves, with the prevalent attitude that if a woman “just kept her legs closed,” she wouldn’t be in this kind of trouble, with the rightwing mentality of control, coercion and cruelty against those outside their circle of concern: Is it really that far in the past? With each eroding away of the painfully slow and hard-fought gains we have made as a society for people with uteruses, for people with mental illness, for people of color, I can’t help but see this frozen-in-time cemetery as a quite plausible reality for the future. It’s not only plausible, this is the past to which forced-birthers want to return. In 2023, pregnant people in red states are endangered and at growing risk of dying in labor, hemorrhaging, contracting serious infections and being forced to carry non-viable fetuses to term even if it costs them their own lives due to laws that would be perfectly at home when the School for Wayward Girls was constructed and running. (Interestingly and probably not coincidentally, it was only after Roe v. Wade was enacted that the institution closed.) Today's "wayward girls" have to travel in secrecy to other states, whether or not they can afford it, to terminate their pregnancies. They are told to wait in hospital parking lots until they are on the brink of death with blood loss before they can get the medical attention they deserve. Today, people in states where abortion is outlawed who want or need to end their pregnancies, and those coming to their aid, have a dangerous and fraught landscape to navigate, one that is becoming more and more reminiscent of the Underground Railroad than anyone should be comfortable accepting. What would the residents of this cemetery, the girls who were never afforded basic freedoms and rights, think about how much progress we have made, only to have these freedoms and rights wrenched away, eroded, reversed? I can only imagine how sad these girls — victims of a bigoted, unjust and sexist society — would be at learning of our country’s regression, driven by a relative few tyrannical ideologues, that puts so many disadvantaged people at such grave risk. Before we left, I walked back to the oak tree. It felt like the branches were sheltering arms over the small cemetery. I found an acorn that had been fused together, two smooth, adorable acorns in one. There was a grave marker for the twin daughters (abbreviated as dau’s) of an inmate named Betty Carroway, newborns who died the day they were born, I presume. This was the spot for the two acorns together, connected by the stem. It felt deeply insufficient but also important to leave this at their gravesite. The twin girls, together forever, symbolized by this simple offering. I don’t know if it brought anyone a small feeling of solace except for me, though. Some of the other grave stones had tokens on them: Scattered coins, crystals, even a statue of a mournful angel. I imagine people who left them felt compelled as I did to acknowledge, to see, to offer just something, knowing full well how ultimately insufficient it would feel. More than acorns and crystals, I think if we can do anything to honor these girls and their babies, we need to strive to be on the right side of history, and if we find ourselves on the side of cruelty, coercion, oppression and unjustness, we must course correct as fast and as fully we can with as few victims as possible. We have to recognize that the cemetery at the Illinois State Training School is not an aberration but a reminder of happens when rights are denied and the lives of our most vulnerable — people of color, people with disabilities, people who are poor, LGBTQ people, people who have had their reproductive systems weaponized against them — are most threatened. Please join the fight for bodily autonomy and personal rights. Anyone who denies rights and freedoms, who values fetuses over actual human beings here on Earth, is squarely on the side the kind of cruelty and oppression that put these babies and girls in these sad little graves. To the buried dead of Illinois State Training School, you are seen. You are seen, and those whose lives are not marked by gravestones but by the trauma and abuse of being born in a punishing time, you are seen, too. We see you, we are fighting for you and we will not forget you. We are also fighting for ourselves and each other.

0 Comments

I reached out to a friend the other day who had recently adopted a paralyzed kitten and I wanted to see how things were going. How was the kitten integrating? I sensed immediately by the pause and then the crack in her voice when she broke the silence that it wasn’t good news. After being assessed by the veterinarians at the clinic my friend trusts, it was determined that the kitten was in far worse condition than anyone involved in her rescue truly realized and would very likely have a short life full of pain and suffering. The difficult decision was made that euthanasia was the most merciful option. My friend, who works full-time from home, was already mentally prepared to care for a cat with inoperable paralysis and in diapers due to her inability to control her bowels, and she was devastated that the sweet kitten she’d had for just a day was in pain with no hope of relief. On the phone, my friend was questioning if anything could have been done, if she could have rearranged her home and her life so the outcome could have been different for the kitten. She has multiple special needs and senior animals and was not apprehensive of the emotional, time and financial resources that this disabled kitten would require. On the contrary, my friend was ready. Knowing that the kitten was suffering and there was no likelihood of reducing it was a different matter, though. She understood that euthanasia was the most humane and compassionate outcome for this kitten but my friend did not make the decision lightly. In fact, she was wracked with grief and self-doubt. I tell this anecdote because it is absolutely consistent with what I have observed in the rescue community: People who will move heaven and earth to help animals in crisis. My friend is one of them. I have been blessed in life to know some truly wonderful people. . . . After college, I started working at a large animal shelter in humane education and that was where I was introduced to the concept of “animal people”. Yes, I was a vegetarian when I started there and then vegan when I left but I cannot say I was ever in the league of these incredible rescuers I came to know. There were the ones who would bring in feral cats they’d trapped every week to get spayed or neutered and pay for their surgeries out of pocket so more kittens wouldn’t be born without homes or care before TNR was a common practice. There were the ones who would spend their winter nights trying to catch loose dogs running in the streets. There were the ones who bottle-fed newborn kittens who were orphaned or abandoned. There were the ones who always adopted the hard to place animals, the seniors, the dogs who were missing limbs, the cats who were skittish. There were the ones who volunteered after work or on their weekends to socialize the cats and walk the dogs, to clean the cages and help tackle the truly endless piles of laundry. And then there were their opposites, the ones who make working at an animal shelter so soul-crushing, the ones who provide ample fodder for a shelter worker’s nightmares. All these years later, they still haunt me. These are the people who would bring in middle-aged or healthy senior animals because they simply no longer want them, knowing that they could die. They would surrender animals because their new love interest didn’t want them. They would move but not look for a place that accepted animals. They would say the dog “smells funny,” the cat is “too affectionate” or, and this is truly one I saw, the companion animal did not match their new couch. There was far worse that I saw at the shelter, of course. I saw dogs brought to us with severe frostbite, kept outside in Chicago all year without adequate shelter. I saw a cat who’d been set on fire, rubbing his raw skin against the wires, purring with contentment at seeing a random person outside his cage, he was still so friendly. I saw survivors of dog-fighting rings and I won’t describe that. I saw skeletal, barely alive animals regularly where you could count every rib. I saw things that I had to immediately block out. The shelter I worked at, like all decent shelters, was a refuge where survivors of human irresponsibility and cruelty had a chance at adoption, but if not – if they were too sick, too old, too unsocialized, too injured – at least they were off the streets, we told ourselves and each other, at least they weren’t suffering anymore, at least they had some moments of human kindness. We held tight to the happy outcomes but were tormented by the others. . . . One of the things I realized early into my five-year stint at the shelter was that ample evidence of the best and the worst of humanity could be found there. It was such an unbelievably wide and stark spectrum. The kindest end and the most heartless end of the spectrum are the people who made the most long-lasting impression on me; same with the animals. The ones who had a perfect outcome and the many who could have only been offered mercy stick stubbornly in my mind 25 years later. The experience of working at the shelter left me with an understanding that was new to me, that our species is capable of extremes of unfathomable cruelty and deep, selfless altruism and love. An animal shelter is where you see those polarities represented in great abundance every day, as well as materialism (“This is a purebred! You should pay me for giving him to you!”), empathy (“There’s a dog tied up in our neighbor’s yard and I wonder if we can do anything,”), entitlement (“I don’t want this cat anymore. Come pick it up.”) and appreciation (“Thank you for the work you’re doing. You are superheros.”) There were people, lots of them, who called with threats, telling us that if someone from the shelter didn’t pick up their animals immediately, they were going to kill them, and there were people, also lots of them, who so loved their adoption experience that they became the best volunteers. So many ways of behaving, so many perspectives, so many different kinds of people. There is something about companion animals, how we think of them and treat them, that brings out the best and the worst of humanity. As opposed to the animals people eat, where even compassionate people generally put on blinders to avoid thinking about it, homeless companion animals are where we see the best and the worst of humanity collide. So much kindness, so much cruelty. I guess my point is, thank goodness for the compassionate ones, the ones who are so far on the side of kindness, the ones like my friend, who was more than willing to turn her life upside-down to give a kitten she had barely met a chance at a good life. This alone gives me hope. I am going to ignore her polarity now so I can just enjoy knowing that she is in the world for a moment. Rest in peace, kitten. You were loved, that much I know. . . .

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed