|

What a small resting place in a subdivision says about our past and why it’s a cautionary tale for the future.

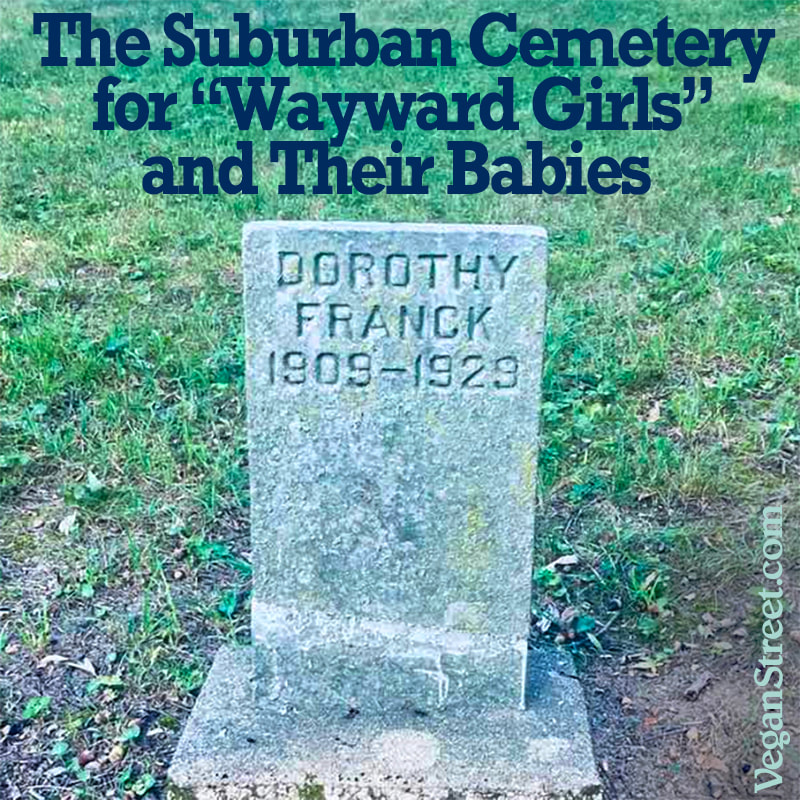

This past Sunday, I was feeling that familiar invigoration I can always rely on in early autumn, as the leaves are just on the verge of changing and the earliest of households start displaying their Halloween decorations. I convinced my son and husband that we should drive out to Geneva, IL, a quaint, verdant river town in the western suburbs of Chicago, about 45-minutes west of us. We trek out here a few times a year to take in the riverwalk, enjoy the boutiques, and breathe in the air of a fresh season. On Sunday, I got that urge again and my guys were on board so we charged our phones, packed our drinks and set out for Geneva. Just before we left, thank goodness, I remembered that there was a place there that I wanted to see in person, one that had not been on our itinerary before. It was the tiny cemetery of 51 graves on what was once part of the 94-acre property of the Illinois State Training School (ISTS), also known as the State Industrial School for Delinquent Girls or the Illinois State Training School for Delinquent Girls (among other appellations), which was in operation from 1894 until 1977. Just outside the gates of the now-demolished institution you fill find this small cemetery, improbably nestled between and behind two large homes in an affluent subdivision called Fox Run. I had heard of the cemetery before here and there and seen some photos of the spare, old gravestones. I also knew that the cemetery was in an unlikely setting but that didn’t stop me from wondering if our GPS had failed us as we drove around cul-de-sacs and saw children riding their bikes and walking dogs in this decidedly residential setting. When my maps program said we had arrived and we were, in fact, between two large, manicured lawns, I stepped out to look around but I was doubtful. Where would it be? After walking around a bit more, I saw the iron fence and called out for my husband and son, still in the car, to join me. Somehow or another, this was it. We walked over to the fence, first passing a plaque, which reads, “Beginning in 1894, this land was used by various government agencies as a center for ‘wayward girls’. The colonial-style cottages, service buildings and fences are gone, but these 51 graves remain. These graves are a testimony that they are no longer wayward but home with their Creator.” The plaque ends simply: “May God’s peace be with their souls.” The first thing I noticed after walking through the gate was how uniform the simple concrete markers were, bringing to mind photos I have seen of the rough gravestones for the Civil War dead. The next thing I noticed before I began looking at the stones was a tall, utterly majestic oak tree, her branches offering a quiet green canopy for us, over much of the cemetery. The acorns crunched under our shoes. That was the only sound in the cemetery — the crunching, that familiar autumn sensation— aside from the occasional words between us as we took the space in. We split up and walked on our own. At first when I saw some gravestones for boys, I was confused because I knew this was an institution for girls but then I noticed how long they were alive: These graves were for babies or newborns. They are clustered together in one section of the cemetery. The adults, sometimes their mothers, are buried near one another elsewhere in the cemetery. The adults were barely adults themselves: The gravestones indicate that age 20 is about the oldest the dead in this cemetery lived to be. That makes sense, though, because ISTS was an institution specifically for minors. The inmates were juvenile girls, some as young as ten, to the age of 18, though some were younger and many were a little older. Most had been sent because they were sexually active or pregnant; later research found that more than 74 percent of inmates were incarcerated at ISTS, which housed up to 400 girls at a time, for reasons of “immorality,” the unspoken code for pregnancy, sexual precociousness or suspected sex work. As the plaque at the cemetery references, they were “wayward” girls, wayward enough to have been convicted in juvenile court. In the mental and physical examination records, it was noted that some were disobedient. Some were described as feeble-minded, which could mean anything from a speech impediment to being terrified of their interrogators. Some were deemed to be incorrigible. Some were found have unpredictable mood swings. Some there had been convicted of truancy. Some were labeled as sexual deviants, a code for lesbians or even non-virgins. Many were runaways from abusive homes. Most were willful. All had been found guilty of violating society’s norms for girls. All were also poor. Middle class and wealthy girls who ran afoul of social norms weren’t given a free pass, but they also weren’t sent to institutions like this one. I have no doubt that some of the girls incarcerated at ISTS over its 80+ year history were indeed mentally ill and genuinely needed help, but that was not what the institution or even society offered at the time. Ophelia L. Amigh, a one-time Civil War nurse who was superintendent of the institution for 16 years, ruled with an iron fist until she was ousted due to vaguely-worded controversies in 1910. To reinforce the obedience to the matrons, girls deemed rebellious or sexually active with each other were sent to the hole (solitary confinement), subjected to “hydrotherapy,” which meant having their bodies repeatedly dunked in cold water, there were well-worn straps and a riding crop, as well as a chair built by the institution’s carpenter, much like a stock from the Puritan days, where the person it is only had their head poking out. They lived in small cells with just a cot and a barred window. I call them inmates intentionally. Many committed to ISTS ran away and were returned; many ran away and were never found. Some like 20-year-old Sadie Cooksey died by electrocution on the third rail of the nearby railroad line as they attempted to flee. The heaviness and the stillness of this residential cemetery is something that sat heavy on my chest after we’d left. Three days later, it’s still pressing down. Inside the cemetery, there was almost the feeling of a gasp that couldn’t be released while I walked through, looking at the stones, taking photos, a kind of suspension. I have visited many old cemeteries and this one probably had the most palpable feeling of sadness. Then again, it could be because of what I know of the place where they died. There is also the unavoidable cautionary tale of this burial ground. All were indigent, all were society’s outcasts, most were teenagers or babies. Some were Black and kept in segregated cottages, others were mentally ill and abused. All were prisoners without resources, and there were some for whom this hellhole was an actual step up from the abuse they faced at home. While the institution has been bulldozed and an affluent subdivision has been planted over it, and the cemetery certainly looks like something from a bygone era, is the ISTS really just a sad chapter of our history? With states having more to rights over the bodies of pregnant people themselves, with the prevalent attitude that if a woman “just kept her legs closed,” she wouldn’t be in this kind of trouble, with the rightwing mentality of control, coercion and cruelty against those outside their circle of concern: Is it really that far in the past? With each eroding away of the painfully slow and hard-fought gains we have made as a society for people with uteruses, for people with mental illness, for people of color, I can’t help but see this frozen-in-time cemetery as a quite plausible reality for the future. It’s not only plausible, this is the past to which forced-birthers want to return. In 2023, pregnant people in red states are endangered and at growing risk of dying in labor, hemorrhaging, contracting serious infections and being forced to carry non-viable fetuses to term even if it costs them their own lives due to laws that would be perfectly at home when the School for Wayward Girls was constructed and running. (Interestingly and probably not coincidentally, it was only after Roe v. Wade was enacted that the institution closed.) Today's "wayward girls" have to travel in secrecy to other states, whether or not they can afford it, to terminate their pregnancies. They are told to wait in hospital parking lots until they are on the brink of death with blood loss before they can get the medical attention they deserve. Today, people in states where abortion is outlawed who want or need to end their pregnancies, and those coming to their aid, have a dangerous and fraught landscape to navigate, one that is becoming more and more reminiscent of the Underground Railroad than anyone should be comfortable accepting. What would the residents of this cemetery, the girls who were never afforded basic freedoms and rights, think about how much progress we have made, only to have these freedoms and rights wrenched away, eroded, reversed? I can only imagine how sad these girls — victims of a bigoted, unjust and sexist society — would be at learning of our country’s regression, driven by a relative few tyrannical ideologues, that puts so many disadvantaged people at such grave risk. Before we left, I walked back to the oak tree. It felt like the branches were sheltering arms over the small cemetery. I found an acorn that had been fused together, two smooth, adorable acorns in one. There was a grave marker for the twin daughters (abbreviated as dau’s) of an inmate named Betty Carroway, newborns who died the day they were born, I presume. This was the spot for the two acorns together, connected by the stem. It felt deeply insufficient but also important to leave this at their gravesite. The twin girls, together forever, symbolized by this simple offering. I don’t know if it brought anyone a small feeling of solace except for me, though. Some of the other grave stones had tokens on them: Scattered coins, crystals, even a statue of a mournful angel. I imagine people who left them felt compelled as I did to acknowledge, to see, to offer just something, knowing full well how ultimately insufficient it would feel. More than acorns and crystals, I think if we can do anything to honor these girls and their babies, we need to strive to be on the right side of history, and if we find ourselves on the side of cruelty, coercion, oppression and unjustness, we must course correct as fast and as fully we can with as few victims as possible. We have to recognize that the cemetery at the Illinois State Training School is not an aberration but a reminder of happens when rights are denied and the lives of our most vulnerable — people of color, people with disabilities, people who are poor, LGBTQ people, people who have had their reproductive systems weaponized against them — are most threatened. Please join the fight for bodily autonomy and personal rights. Anyone who denies rights and freedoms, who values fetuses over actual human beings here on Earth, is squarely on the side the kind of cruelty and oppression that put these babies and girls in these sad little graves. To the buried dead of Illinois State Training School, you are seen. You are seen, and those whose lives are not marked by gravestones but by the trauma and abuse of being born in a punishing time, you are seen, too. We see you, we are fighting for you and we will not forget you. We are also fighting for ourselves and each other.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed